No matter how many books, blogs and other accounts you read of cruising the canals and of the experiences of others, nothing really quite prepares you for the reality of navigating a large old steel boat along narrow waterways, living on it every day and coping with the challenges thrown your way.

For the sake of the record, we might try to list a few of the things we found confronting us, the little things we found that made life interesting, or more comfortable, and the things we might like to change or improve for future seasons.

Every person, and every crew, is different in their preferences, tastes, expectations and ambitions. So these are personal observations, even if a few of them seem to have greater universality than others.

How to be very glad you bought a boat that was already well-equipped and in excellent condition

Some people have a desire to buy a “project”; we didn’t. It was wonderful to be able to set off on our adventure without spending months renovating, redecorating, equipping and setting up our boat. We had probably 80% or more of what we needed, and the remainder was easy to buy and fit or stow. From major equipment (like a recently-rebuilt engine and a generator in good working order) down to sheets and towels and plates and cutlery, Eben Haezer was pretty much ready to go and much of what we bought were personal choice items.

To a large extent this was because we bought a boat that was lived on full-time by a professional experienced boatman, rather than a part-time cruiser being sold by someone from another country who only used the vessel a few weeks or months a year.

The previous owner, Pierre, bless his heart, left us with a fairly comprehensive set of mechanical tools, engine spares including belts, filters, automatic shaft greasers, cleaning cloths, oils and lubricants and cleaners.

All the important systems and major pieces of equipment on the boat – engine, generator, water and waste pumps, toilet, water heating, central heating, electrics, water tank and plumbing, cooking range and range hood, combi-oven, lighting, radios, steering lines, ground tackle and ropes, fenders, fuel tanks and lines, communications/navigation equipment and antennae, washer/dryer, portable A/C unit, refrigeration – were in excellent or near-new condition.

This is a fantastic advantage in setting off with confidence, with minimum fuss, and in superior comfort in one’s first season of cruising.

How to wish you had more documentation and/or time to learn how all these wonderful systems work

This was our own fault, I guess, since we had more than adequate time to bother the previous owner to go through (just once, more, please ?!?) how to operate or understand the mysteries of the electrics, pumps, boilers, engines, gears, greasers and so forth. But really, in the end, how much time can you expect him to spend on teaching you what he no doubt thinks you should know already?

On the other hand, there was in our case, probably the same as for just about everybody on every boat, a distinct lack of documentation – operations booklets, manuals, spares lists, etc, for the boat’s major systems and equipment. We should spend time collecting what we can from the internet and other sources. It will take time, but it will be worth it for us in the end and might form a legacy to any new owner when the time comes to sell our boat.

How to be grateful for, or reconcile yourself to, the systems, set-up and equipment you have, and what you might add

Engine, cooling, transmission, drive and steering

Our engine is a DAF575, a true workhorse of canal barges pushing out 110 horsepower. Made in 1973, rebuilt in 2014 with only 182 hours when we bought her, she is reliable, worry-free and powerful enough for our needs.

The transmission and drive are strong and simple. I haven’t actually identified the make of transmission (still trying) but it works! The shaft has three greasing points, equipped with SKF System 24 “set-and-forget” automatic lubricators. These are marvellous little things, gas-operated, which you dial to pre-set the rate of lubrication and then just check annually for replacement. We also have manual lubricant injectors in reserve in case we ever need to override the automatic system.

Steering – simple chain and cable system. With a big wheel, heavy rudder and some 30+ tonnes of displacement, it works well and easily and, we hope, never or rarely suffers a breakdown – in which case we have replacement cable which is easily and quickly fitted, even in an emergency. We would never go hydraulic, which is complicated, sensitive, maintenance-heavy… all the wrong words.

Engine cooling – we are lucky enough to have a closed system, rather than a raw water cooling set-up. No inlets, no filters, no pumps and no impellers. Driven by engine pressure, cooled along the hull, it just goes and goes. Never a fear of impellers disintegrating; never a need to clean weed and other debris from the inlet or the filter. We have heard of, and spoken directly to people who suffered it, boats who have had to stop every few hours in a heavily-weeded section of canal just to clear their inlets and filters. Not a problem for us!

Power and electrics

Our system is set up to select between no power, shore power, generator or main engine for the source of electrical generation/supply. Shore power and the generator provide 230v AC; the battery circuit is 24v DC, stepped up to 230v via a 3000-amp inverter and stepped down to 12v for controls, radios, etc. As far as it goes, it works well, although there are a few eccentricities in the circuit design, and an unfortunate spaghetti complex of wiring which one day we will get organised.

The generator is a Lister 7Kv unit, not new but reliable, air cooled and fueled with red diesel (much cheaper!) stored in a dedicated steel tank. It has a separate 12v starter battery and is remotely activated via a starter button and kill switch in the forward cabin, and also on the gen set itself. When running, it supplies more than enough power for all our needs. It is also noisy and creates a lot of vibration, being a BIG unit, located in the forward well. If you started out new, you may well decide to buy a much smaller, modern, silenced unit in a muffler box. But we have what we have and it does its job when required, which is not often enough to worry.

We learned early on that access to shore power requires (1) a lot of extension and (2) a multitude of connectors. So we have our basic shore power lead plus another 40 metres of extension lead, plus connectors that match two-point and three-point, male and female junctions. Since we tooled up in that area, we have no problems.

No problems, that is, as long as the power supply is reliable. On-shore power supply is generally 10amp, rarely 15amp, but sometimes as low as 6amp in smaller moorings or where you have to share a point with another boat via a splitter. It means you have to be constantly aware how much load you place on the supply at any given time.

We also have a small solar system, basically two rigid panels on the wheelhouse roof and a small regulator, ostensibly providing a trickle charge to our house batteries. I am not sure how much charge they are producing, to be honest, and the panels look to be a bit old. We will definitely look to upgrade this system in the future.

Cooking, heating and cooling

We were concerned at first to find that the stove was a domestic style four-burner electric set; we have always preferred cooking with gas and we were concerned the drain on power would be a problem. We were persuaded, though, when we met so many professional boatmen in Belgium who refused to have gas on board (for reasons of safety) and the cost of installing a gas system – external fixed steel ventilated gas box, plumbing and a new range. With shore power we are OK; otherwise the generator supplies more than enough and even then we only need it for an hour or less. One thing we would like to investigate is a two- or three-burner inducton cooktop to replace the old iron-element four-burner.

We inherited a counter-top combi-oven – a combination of microwave and convection over/grill – that proved to be a marvellous bit of kitchen kit. Programmable or manual, it made thawing, roasting, grilling, baking and reheating very easy and power-efficient. Thoroughly recommended, and less power and space than a conventional oven.

Being Australians, we were sure bbqs would be an important part of our cooking mix, so we bought two small units – one gas and one charcoal-burning. As it turned out, we used them less than we thought we would, but they are both wonderful. We have cooked/baked whole coquelettes, and many, many sausages and brochettes, both vegetable and meat-based, and even on occasions things like rice and pasta. We prefer the charcoal bbq but use gas for quick convenience. The French are not huge users of bbqs but when they do, they love masses of smoke!

The final piece of our cooking/kitchen kit which we added was a coffee machine and grinder. We’re happy with a plunger (French press) but there is always the problem of disposal of the grounds – on a boat, harder and messier than you might think. Our espresso machine is nothing flash but it delivers an adequate shot…. regrettably but also thankfully, better than 90% of the stuff you might be served in a French café!

Heating is provided by our central heating system with a diesel-powered Kubola boiler and six radiators throughout the boat. It’s fabulous, cheap and finely adjustable and could easily sustain us through the harshest French winter. We would never consider a solid-fuel stove because (1) it takes up a lot of space, which is at a premium anyway (2) it requires sourcing and storage of fuel – wood or briquettes or whatever, which is a hassle and another space-destroyer (3) it needs another hole in the deck for the chimney, and holes are always potential leak-points and (4) really guys, it’s romantic but it’s dirty! Needs cleaning every day, lots of ash, lots of tar on the chimney… nooooo!

Cooling is basically open doors and windows, plus two or three small fans for circulation. We were bequeathed a small portable air conditioner with a window exhaust, which we used on some of the hottest summer days but was never really a central part of our climate control. Nice, but not essential.

Mooring and ground tackle

We have a massive anchor with many metres of heavy chain, and a massive manual winch to which an electric winch has been added, driven off the generator. Anchors on inland waterways are basically emergency equipment, and we have never used it. In fact, we are not certain we know how to… something we should probably put on our to-do list.

Eben Haezer has heavy duty double bollards on either side at the bow, and single bollards aft, plus multiple belay points fore and aft and at intervals along the gunwales. We were bequeathed four x 20-metre lengths of good quality rope for regular lock work and mooring, plus extra heavy-duty nylon rope for long-term mooring. We found the system of having four sufficient lengths of rope – one for each side fore and aft – by far the best system for fast adaptation to situations such as locks and port moorings, without needing to swap ropes from one side to the other at the last moment. Plus we found that in many locations, the more mooring lines the better, two at each end secured in opposite directions, gives greater security and stability.

Before leaving Schoten we had four mooring stakes made up for us from short lengths of angle iron, sharpened at one end at with a flat plate welded to the other end for banging in with a heavy mallet. We only used these a few times but found them very useful for when there was no bollard available on shore. Best to use them in pairs, hammered into the ground at cross-angles; otherwise you might find them easily dislodged by the wash of another passing boat.

We also made up a passarelle, or boarding gangplank. Ours is simply a sturdy ladder with sections of thick marine ply and checkerplate secured to one side. This provides a safe, secure – and cheap – gangway for accessing the shore when the ground is much lower than the deck, or uneven, or otherwise requiring a jump. It came in handy on many occasions.

We inherited a set of fenders when we bought Eben Haezer. These included four solid composite glissoires – long, narrow fenders that protect the bow and stern on each side. We also had four heavy-duty inflatable fenders, one at each end and each side. This are primarily for additional protection and should not be used to take the full brunt of any contact, as they would simply pop under the weight of the very heavy boat (as one did!). Despite this protection, we still managed to bump and scrape the hull from time to time; at first we worried mightily about this but we became used to it, as other boaters seemed to, and we just kept our brushes and paint handy for periodic touch ups.

Navigation

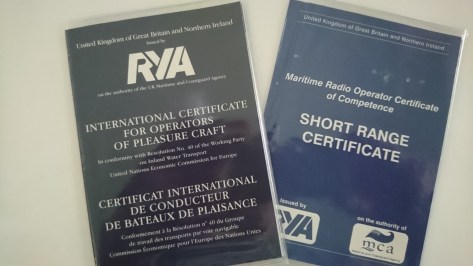

We inherited a laptop, loaded with software from PC-Navigo, connected to our AIS (Automatic Identification System), which allowed us to plan and monitor our travels. You could get by without it (unless you are over 25 metres in length, in which case it’s compulsory) but we found it fantastic – for planning our journeys, seeing any operations (such as locks or lift bridges) ahead, and monitoring our progress in real time. Plus it told us when any other large vessels were approaching, from ahead or behind, allowing us to take whatever action we thought necessary to avoid or avert. Very reassuring!

Lighting

The wheelhouse is the only place with 12v overhead lighting – running off the same stepdown converter as the radios, AIS and other control equipment – meaning the “bridge” had lighting whether or not shore-power or 230v inverter power was available. The rest of the bat is equipped with 230v lighting, running off the inverter, which we think is perfectly fine, given the low current draw. We are not great fans of the lighting design or fittings, though, and it proved to be difficult to find replacement bulbs/LEDs for them, so we will probably replace those in the future. For 2016, it was no problem.

Refrigeration

We inherited a full-size domestic upside-down frig-freezer, which we adore. It uses the majority of our daily power draw, but who cares. We buy fresh as often as we can, but we love to buy lots of good food, and when you are not sure when you can next buy a good piece of beef or a succulent free-range whole chicken, or a pack of lovely laminated pastry or whatever, a freezer is a precious thing. We love it, and we knew we were never going to compromise with a teensy bar fridge, eutectic camper-style chamber or an ice box.

Water

We have a rigid plastic water tank in the rear of the boat that holds 1100 litres. For two people this is quite adequate, although we found it amazing how quickly we can go through it. We fill up at every – I mean EVERY – opportunity we get and so never found a time when we were short of water…. although we frequently came across other boats, mainly hire boats, who moored up and rushed to the water taps to replenish their exhausted supplies – mainly, we suspected, because they had simply shunned opportunities to fill when they could.

Early in the season we found it necessary to stock up on extra lengths of hose, for those surprisingly frequent occasions when the taps were located too far from the boat. We also learned to have a box of fittings of various types and dimensions, since French villages, towns, ports and moorings have agreed to disagree on standardisation. Plus you need spares – because inevitably you will leave a fitting behind at some stage.

For hot water, we have a small immersion-coil electric heater in the bathroom, providing hot water to kitchen sink, shower and hand basin. Some people love the idea of a boiler running off the main engine but for us that’s an expensive addition to the piece of machinery that’s central to your motive power and the small room it’s located in. For us, if we cruise for a few hours the power that the engine generates is sufficient to heat enough water until the next day; or we can simply plug into shore power (which we would pay for anyway).

Bathroom and laundry

We love our bathroom, set up as it is in a domestic style rather than a pokey shipboard manner. We have a basin set into an expansive vanity – believe me, even in a shipboard bathroom, having plenty of surface for your odds and ends is wonderful, especially when it doubles as your laundry. We have a small bath – I guess what you would call a three-quarter bath – with sufficient room to stretch out in or to take a perfectly adequate sit-and-crouch shower using the hand-held rose. Ideally, we would lift the deck height above the bath to enable a standing shower but, as it is, it is perfectly comfortable and efficient, as well as space-effective.

The toilet is a macerating marine toilet, with a plumbed cistern flush system. Apart from the noise it makes when the waste pump operates, you would not really know you were not using a standard domestic flush toilet. Gotta love it! We do not have a blackwater holding tank – there isn’t much point, since there are hardly any pump-out points in France, so you would be reduced to pumping out a couple hundred litres of the stuff at the unfortunate place of your choosing, rather than one flush at a time.

Our bathroom also holds a front-loading washing machine and a condenser dryer. They are both marvellous pieces of kit which we love. We could, if we were forced to, take our clothes to local laundromats, of which there are plenty in France although sometimes located at a fair remove from the mooring, and always requiring coins or tokens which you may not have on hand. With our own washer we can wash wherever and whenever we are, independent of the weather and location. Kind of like at home, right? The condenser dryer, instead of blowing hot air onto the clothes and out into the laundry, extracts moisture before draining it away as condensed water into a separate reservoir, reducing both heat and moisture inside the boat.

General appearance, fit out and decor

Some people love everything to be sleek and modern; others like it all to be olde-world, all varnished wood and polished brass. We sit somewhere in the middle. Eben Haezer is 100 years old and has graceful old-fashioned hull lines. Her superstructure and interior fit-out is much newer and to a very large extent is pragmatic more than romantic.

Interior linings – walls and floors – are modern composite materials, and most of the woodwork in the wheelhouse is also non-traditional, much of it simply painted white. The windows in saloon, bathroom and cabins are large, aluminium-framed, sliding style. The advantage of this modern fit out is the work and cost of upkeep – both minimal – but the downside, if there is one, is an absence of “atmosphere”. We decided we quite liked the space and ambience and lightness of the interior; tempting though it is to introduce a traditional touch with wooden linings and brass fittings, we are probably better off spending that money on good quality decor such as light fittings, cupboards, chairs, rugs and other stuff.

Entertainment

Most liveaboard boats and every camper van in Belgium and France comes with a satellite dish and big TV, so we thought we would follow suit. We bought a large flat-screen TV in Schoten and a satellite decoder and signal detector in Antwerp (the boat already came equipped with a dish). They work fine and we had access to dozens of channels in English. As time went on, though, we found we really didn’t watch too much; we’re not big consumers of TV, even at home. Butwe have for when we want it, so all good.

Music is provided in the wheelhouse via a car radio in the overhead console, with good but not great speakers. We plugged my phone into the radio to access the playlist stored on the phone, or via streaming services when we had a free signal or felt we could afford to burn some of our data allowance. The system is adequate but at some stage we will probably upgrade and extend the system to the saloon.

External spaces

Eben Haezer has a large elevated rear deck which provides a lovely space to sit and enjoy a drink or alfresco meal, and to entertain visitors. In Schoten our good friend Roland took us to a place where we could buy luxurious thick-pile artificial grass matting at great prices. We wish we had not baulked at the idea, because it would have provided excellent cover. The deck gets quite on a hot sunny summer’s day, and the matting would have insulated the deck as well as being kind to bare feet. If we find good quality turf matting at a decent price, we will probably go that way.

Shade on the deck is provided by a large market umbrella which we inherited. It works very well but requires regular moving to match the movement of the sun and, because of its size and weight, it doesn’t tilt. We have thought about a fitted marine canopy or large bimini, but these are very expensive and, until we work out a good design, we’ll deal with what we have.

We also inherited a huge metal and glass outdoor table and four lovely outdoor chairs – large, adjustable, folding. The chairs are great but the table is just way too big. When and if we find a smaller version we like, we will swap, for sure, giving much more space on the rear deck but still allowing for eating, relaxing and entertaining.